CHAPTER 12: FACULTY DIMENSION

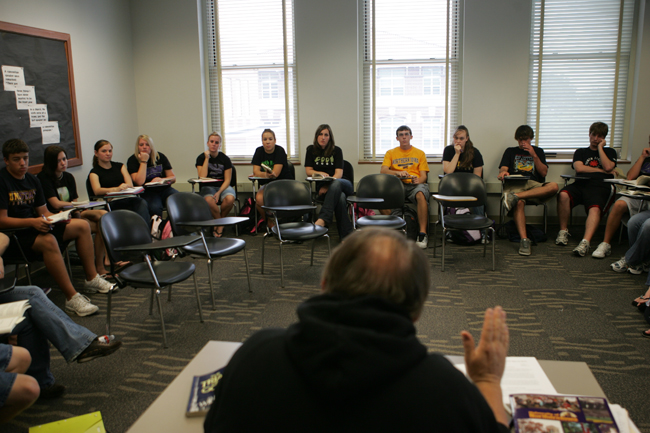

Foundations Institutions make the first college year a high priority for the faculty. These institutions are characterized by a culture of faculty responsibility for the first year that is realized through high-quality instruction in first-year classes and substantial interaction between faculty and first-year students both inside and outside the classroom. This culture of responsibility is nurtured by chief academic officers, deans, and department chairs and supported by the institutions’ reward systems.

Key Performance Indicators for the Faculty Dimension include:

- Encouragement: senior academic leaders encourage the use of pedagogies of engagement in first-year courses, the understanding of campus-wide learning goals for the first year, the understanding of first-year student characteristics at UNI, and the understanding of broad trends and issues in the first year.

- Unit Level Engagement: unit level academic administrators encourage faculty to use pedagogies of engagement in first-year courses, to understand unit-level learning goals for first-year courses, and to understand the discipline-specific trends and issues related to entry-level courses.

- Expectations: expectations for involvement with first-year students are clearly communicated to new faculty during the hiring process.

- Rewards: the institution rewards a high level of faculty performance in instruction, out-of-class interaction, and advising for first-year students.

Back to Top

Current Situation

Encouragement

In evaluating the level of encouragement from senior administrators for excellence in teaching during the first year, the committee examined a number of key institutional documents, including the University Strategic Plan, policies and procedures, and the United Faculty Master Agreement. There is little evidence of any coordinated effort by senior academic leaders to encourage faculty to focus on the first year. The University Strategic Plan for 2004-2009[1] contains objectives that can be assumed to include first-year students as a target for attention. However, none of these, as stated, identifies the unique academic, social, and developmental challenges faced by new students.

Table 12.1 indicates aggregated responses to faculty and staff survey questions related to administrative support of faculty involvement with first-year students. Respondents were asked, “To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by institution leaders?” (Q54) Overall 45% of faculty/staff indicated the degree was high or very high, and the mean was 3.29. Looking at the sub-categories of respondents, however, reveals a significant difference in the perceptions of administrators and faculty on this issue. Over half (52%) of administrators indicated that the degree was high or very high, while only slightly more than a third (33%) of faculty respondents indicated that the degree was high or very high. Other evidence regarding the lack of campus-level encouragement is demonstrated by the fact that only 10.8% of faculty, staff, (with a mean of 2.20) responded high or very high when asked, “To what degree do you, as a faculty/staff member, have a voice in decisions about first-year issues?” (Q28), and that only about 37% of faculty/staff (with a mean of 3.14) answered high or very high when asked, “To what degree does this institution assure that all first-year students experience individualized attention from faculty/staff?” (Q47)

Table 12.1 Faculty/Staff Survey – Faculty/Campus Culture

| Question # | Question Text | Responded 1 or 2 | Responded 3 | Responded 4 or 5 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | To what degree do you, as a faculty/staff member, have a voice in decisions about first-year issues? | 63.9% | 25.3% | 10.8% | 2.20 |

| 47 | To what degree does this institution assure that all first-year students experience individualized attention from faculty/staff? | 25.4% | 37.5% | 37.1% | 3.14 |

| 54 | To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by institution leaders? | 23.2% | 31.8% | 45% | 3.29 |

| 55 | To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by your department/unit leader? | 19% | 24.2% | 56.8% | 3.53 |

| 56 | To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by your colleagues? | 21.3% | 30.1% | 48.6% | 3.37 |

| 69 | During the hiring process at this institution, to what degree are faculty responsibilities related to first-year students addressed by position descriptions? | 68.8% | 14.9% | 16.3% | 2.10 |

| 70 | During the hiring process at this institution, to what degree are faculty responsibilities related to first-year students addressed by candidate interviews? | 65.1% | 17.2% | 17.7% | 2.21 |

| 72 | During the new faculty orientation at this institution, to what degree were your responsibilities related to first-year students addressed? | 73.5% | 14.3% | 12.2% | 1.94 |

1=Not at all; 2=Slight; 3=Moderate; 4=High; 5=Very High

Some faculty members (n=172) also voiced concerns about teaching first-year courses, when asked about variables which affect their willingness to teach first-year courses, in an open-ended question on the FoE faculty/staff survey. Numerous reasons were offered, including large class size (33%, n=59), the maturity levels and preparedness of first-year students (16%, n=29), and lack of knowledge about the Liberal Arts Core (e.g., objectives/purposes of the courses in it) (17%, n=30). Specific comments from the FoE faculty/staff survey open-ended question identifying the top three weaknesses in the way the college conducts the first year (n=283) include the following: (a) lack of a coordinated approach to the first year (16%, n=44); (b) insufficient academic support for first-year students outside the classroom (13%, n=36); (c) lack of adequate faculty resources for instruction for first-year courses (i.e. classes are too large, not enough classes offered, not enough classes taught by tenured and tenure-track faculty) (12%, n=34); (d) lack of support for diverse students and lack of diversity at UNI (7%, n=20); (e) lack of coordination of efforts regarding first-year students across different units in the university (6%, n=18); and, (f) lack of faculty/staff awareness of programs focused on the first year of college (6%, n=18).

Faculty and staff were also asked about the top three strengths regarding the way UNI conducts the first-year of college. They (n=276) named academics (23%, n=93), a student-centered campus (20%, n=81), the faculty and staff (19%, n=80), advising (16%, n=65), co-curricular programs (12%, n=51), and the campus environment (10%, n=40).

According to the Faculty Survey of Student Engagement (FSSE) administered at UNI in 2007, 74% of faculty who taught first-year students reported that they spend 1-4 hours per week, “Reflecting on ways to improve my teaching,”[2] but at present there is no formal institution on campus to coordinate such activities. In recent years, efforts have been launched to reestablish the Center for Excellence in Teaching, which was closed in 2001 due to budget constraints and following the departure of the center’s director. In the absence of a Center, some 21 topic-focused faculty seminars (large group lecture, classroom decorum issues, what students want in syllabi, etc.) were held during the 2005-2006 semester. About 60 members of the faculty, as well as a few students, participated in one or more sessions. In the following year, only three or four sessions were held following a change in faculty leadership for this effort. The College of Humanities and Fine Arts offered a workshop in fall 2008 on college classroom inquiry. While there has been ongoing interest among at least some faculty regarding professional development related to teaching, limited administrative support has made it difficult to sustain a campus-wide effort in this area. And none of the limited efforts thus far have focused specifically on teaching first-year students.

Unit Level Engagement

Survey results reveal that faculty and staff believe that unit-level administrators are slightly more encouraging of faculty involvement with first-year students than were senior-level administrators.

When asked, “To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by your department unit/leader?” (Q55), UNI met the benchmark of 3.5, however, there was a marked difference in perceptions between administrators and faculty on this issue: 71% of administrators but only 46% of faculty reported high or very high. Additionally, administrators report that their colleagues consider faculty involvement with first-year students important at a rate of 53% for high or very high, compared to 39.5% for faculty when asked, “To what degree is faculty involvement with first-year students considered important by your colleagues?” (Q56) This is again an indication of contrasting perceptions between faculty and administrators.

While the Liberal Arts Core is not synonymous with  first-year courses, for many faculty their experience with first-year students is primarily through the LAC. Department resources and other demands (e.g., offering enough major courses) may lead to the situation where first-year and LAC courses may be devalued. Evidence of this lies in the relatively high number of first-year courses taught by adjunct faculty. From fall 2001 to spring 2008, the average percentage of Liberal Arts Core (LAC) sections taught by non-tenure track faculty was 42%. This number is not markedly different when all first-year courses are included (43%).[3] It should be noted, though, that there are many complexities associated with staffing these courses and that UNI may need to rethink the curricular, pedagogical, and fiscal approach that departments have had to take to satisfy these LAC requirements.

first-year courses, for many faculty their experience with first-year students is primarily through the LAC. Department resources and other demands (e.g., offering enough major courses) may lead to the situation where first-year and LAC courses may be devalued. Evidence of this lies in the relatively high number of first-year courses taught by adjunct faculty. From fall 2001 to spring 2008, the average percentage of Liberal Arts Core (LAC) sections taught by non-tenure track faculty was 42%. This number is not markedly different when all first-year courses are included (43%).[3] It should be noted, though, that there are many complexities associated with staffing these courses and that UNI may need to rethink the curricular, pedagogical, and fiscal approach that departments have had to take to satisfy these LAC requirements.

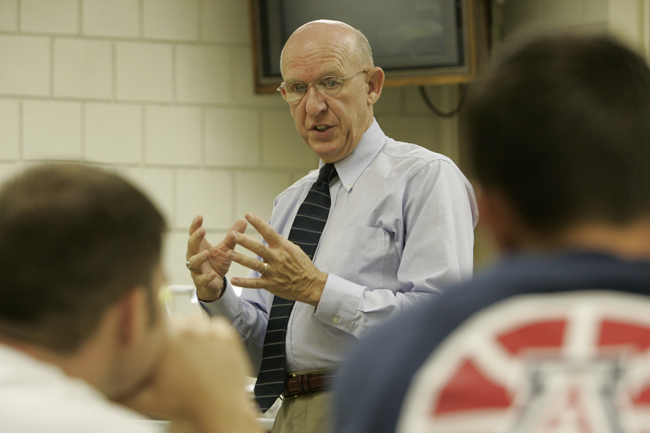

Expectations

Expectations for new faculty members are delivered in part via faculty orientation, an event for newly hired tenured and tenure track faculty conducted just prior to the start of the fall term. The orientation consists of welcomes from senior administrators and sessions on a variety of topics of interest to faculty, including teaching, research, benefits, and student services. There is no session dedicated to a discussion of transition issues or other information specific to first-year students. The faculty and staff survey data support the finding that expectations for involvement with first-year students are not communicated to newly hired faculty in a systematic way. When faculty were asked, “During the hiring process at this institution, to what degree are faculty responsibilities related to first-year students addressed by position descriptions?” 69% reported not at all or slight. (Q69)

In addition, during committee meetings, numerous discussions centered on the knowledge of the first year and personal experiences during the hiring process in which a first-year focus was never discussed. When faculty were asked, “During the hiring process at this institution, to what degree are faculty responsibilities related to first-year students addressed by candidate interviews?” 65% reported not at all or slight. (Q70) When faculty were asked, “During the new faculty orientation at this institution, to what degree were your responsibilities related to first-year students addressed?” (Q72), 74% responded not at all or slight.

Data from the 2007 administration of the Faculty Survey of Student Engagement (FSSE) might provide some indication of the “felt” culture at UNI related to expectations for involvement with first-year students. Table 12.2 below shows that over two-thirds of UNI faculty who teach first-year students think the institution emphasizes providing students with support to succeed academically; around half or slightly fewer see an institutional emphasis on encouraging students to become involved in developmental activities outside of the classroom. Only 35% of faculty teaching first-year students believe that the institution emphasizes providing students with assistance with non-academic responsibilities, and even fewer (22%) think the institution emphasizes providing students with support to thrive socially.

Table 12.2 Comparison of Faculty and Student Perceptions of Institutional Emphases[4]

| The institution emphasizes the following: | Percentage of faculty who teach first-year students responding very much or quite a bit | Percentage of first-year students responding very much or quite a bit |

|---|---|---|

| Providing students the support they need to help them succeed academically. | 68% | 79% |

| Helping students cope with their non-academic responsibilities (work, family, etc.). | 22% | 26% |

| Providing students with the support they need to thrive socially. | 35% | 42% |

| Encouraging students to attend campus events and activities (special speakers, cultural performances, athletic events, etc.). | 43% | 65% |

| Encouraging students to participate in co-curricular activities (organizations, campus publications, student government, fraternity or sorority, intercollegiate or intramural sports, etc.). | 49% | (No comparable question on the student survey) |

Rewards

In general, there is little evidence that there are reward structures in place that focus on instruction,

out-of-class interactions, or advising with first-year students (see Table 12.3). Faculty and staff were asked in the FoE survey, “To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by faculty colleagues?” (Q58), and only 16% of faculty/staff said to a high or very high degree. When asked, “To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by department/unit leaders?” (Q59), about 25% of faculty/staff reported a high or very high degree. Finally, when asked, “To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by institutional leaders?” (Q60), only 12.2% of faculty/staff felt that they did at a high or very high level.

Table 12.3 Faculty/Staff Survey - Rewards

| Question # | Question Text | Responded 1 or 2 | Responded 3 | Responded 4 or 5 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by faculty colleagues? | 56.7% | 27.8% | 15.6% | 2.38 |

| 59 | To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by department/unit leaders? | 43.1% | 32% | 24.9% | 2.67 |

| 60 | To what degree is excellence in teaching first-year students acknowledged, recognized, and/or rewarded by institution leaders? | 62.2% | 25.6% | 12.2% | 2.17 |

1=Not at all; 2=Slight; 3=Moderate; 4=High; 5=Very High

The processes for promotion and tenure review are laid out in the Master Agreement. Each academic department head and department Professional Assessment Committee (PAC) independently evaluates annually the teaching, research, and professional service of faculty on probationary status prior to making recommendations to continue probation, or to grant tenure or promotion.

Salary increases are based partially on merit, and merit increases are determined by department heads proposing salary increases to their respective deans. The criteria used by department heads to recommend merit increases vary from department to department. Many departments have detailed procedures for assigning merit, and consider research, teaching, and service accomplishments in their final determination. For the new Master Agreement (2009-2011), department heads need to develop evaluation standards for merit increases based upon individual assignments and are required to explain the rationale for determining the merit increase for each case.

In addition to salary, there are several awards and funding opportunities that recognize excellence in research, but there is less support for professional development in teaching. The funding opportunities for research include professional development assignments (designed to support faculty research, creative activities, or completion of a terminal degree), and four- and eight-week summer fellowships (designed to support faculty research, creative activity and grant applications). The summer fellowship guidelines exclude teaching-related activities, stating that, “professional training experiences; curriculum development that is judged to be of a routine nature and thus an expected part of teaching responsibilities; and travel whose primary purpose is to enhance classroom presentations,” will not be eligible. Of course, it is perfectly reasonable to have specific awards directed toward research and creative activities; however, the lack of an explicit reward structure that values and encourages teaching, or for first-year teaching in particular, are causes for concern.

One notable exception is the Excellence in Liberal Arts Core (LAC) Teaching, which is a new teaching award that was initiated in 2009 and recognizes excellence in teaching courses in the Liberal Arts Core.[5] The emphasis for this award is placed on the overall quality of teaching, which is not limited to the classroom. This award states outstanding teaching includes assisting students outside of the classroom and demonstrating serious commitment to academic excellence and individual student needs, interests, and development. Faculty recipients of the LAC award may choose to accept the award as supplies-and-services funds to offset expenses for curricular development and/or research or creative activities, or as a monetary award. It should be noted that the LAC does not consist of all courses taught in the first year, or of all teaching and services activities that faculty engage in with first-year students.

Academic advising represents an important teaching function that does not appear to be recognized in promotion and tenure decisions. If advising is to be considered in the recognition and reward for faculty, the University must clearly define the value and expectations of academic advising, including having in place an institutional mission, vision, and goals for academic advising. Furthermore, and most importantly, the "service" of academic advising must be specifically recognized and included in the consideration for tenure, promotion, and merit decisions. Essential to successful recognition and engagement by faculty (and all academic advisors) are professional development opportunities and an assessment plan for evaluation of academic advising throughout campus.

Back to Top

Opportunities and Challenges

- There is a general belief among administrators and faculty that the institution is committed to the success of first-year students based on responses to the question, “Do you believe that this institution is committed to the success of first-year students/freshmen?” (Q16 FoE faculty/staff survey). Well over half of administrators (69%) and slightly over half of faculty (53%) are in high or very high agreement with this question. In view of this commitment, additional support for faculty members teaching first-year classes would be beneficial.

- At UNI, on average, over half (57%[6]) of first-year courses are taught by tenured or tenure-track faculty. There is very little training done with these faculty or with the remaining instructors, comprised of adjuncts, temporary instructors, or GTAs.

- Open-ended responses on the FoE faculty survey contained 172 faculty responses that indicated concerns about teaching first-year courses. Reasons cited included: concerns about the LAC, class size, student maturity or preparation, course load, lack of support, and a desire to teach upper-level courses.

- In looking at day-to-day preparedness for class, within our own student population, well over half of students reported in the 2009 NSSE that they sometimes (61%), often (13%), or very often (4%) come to class without completing readings or assignments.[7]

Back to Top

Recommended Actions

1. Develop a Comprehensive Plan for Faculty Development for Teaching

a. Educate the faculty about first-year students, the importance of a positive first-year experience, and how they can participate in ensuring a positive first-year experience. This should be an organized effort, developed with faculty and student affairs input, and administered by Academic Affairs.

b. Create a subsection of the summer fellowship award to include a 4-week summer fellowship option specifically reserved for those who want to submit proposals to engage in substantial curricula or pedagogical enhancement or development. The first few years of this award could be targeted to first-year teaching, and could broaden after that to include other teaching enhancement or development projects.

c. Fund a Center for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning or other entity that ensures opportunities for faculty development.

2. Provide Incentives to Promote the Idea that Teaching and Advising of First-Year Students is Valued

a. Amend tenure and promotion processes to better reward excellence in teaching and advising first-year students.

b. Include academic advising responsibilities as a function of teaching and provide minimum training for all faculty advisors.

c. Designate a percentage of merit pay increases given to department heads to be devoted to rewarding faculty who teach first-year courses, especially those who teach them excellently, and for those faculty who advise first-year students.